In the Getting Started topic I looked in a little detail at the word and phrase repetition checks and gave an overview of how the results lists worked. All the results lists in SmartEdit look, feel and work in the same way. If you haven’t read the Getting Started topic, you should do so before continuing.

The button and menu options on the SmartEdit toolbar allow you to run individual checks or groups of checks. If you wish to run every check on your document you can do so by clicking the “Run all Checks” button (second from the left). On an 80,000 document, you should expect this to take a couple of minutes. For a smaller, short story sized work, maybe 20 seconds or so.

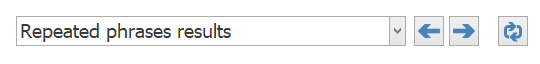

After completing the checks, the results section will open inside Word to the left of the document and the first set of results will be visible. This will usually be the Repeated Words list. You can navigate to a different results list by opening the drop down and choosing different results, or by clicking the left or right arrows as shown below.

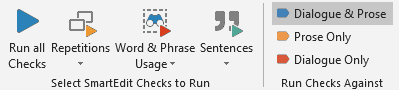

Whatever checks you choose to run, you have the option of running those checks against your entire document (dialogue and prose), prose only or dialogue only. The default is your entire document, but you can select Prose or Dialogue from the toolbar buttons shown below. This is a feature that is used by some writers to run a series of checks on character dialogue, or to exclude that dialogue from any results.

For example, you may wish to keep a check on adverbs in your prose and may not be interested in adverbs used by your characters in speech. Or you may wish to seek out clichés in dialogue only.

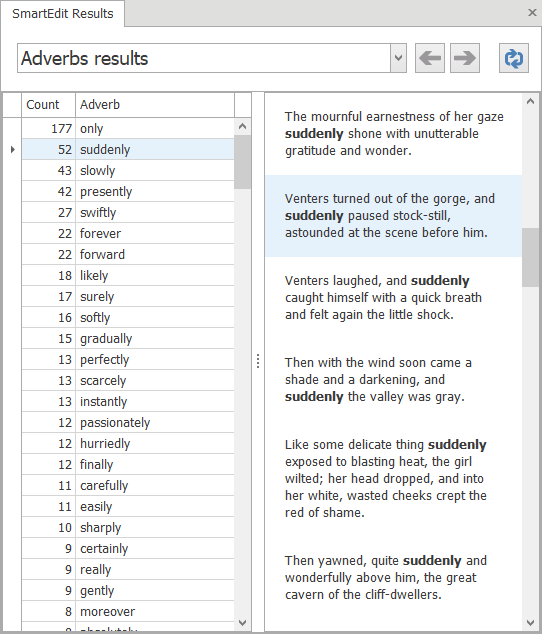

Let’s take a look at some of the results produced by SmartEdit for “Riders of the Purple Sage,” beginning with adverbs. Many writers attempt to limit their use of adverbs and SmartEdit provides a quick and easy way of checking each adverb for overuse and fixing the problem there and then.

Zane Grey makes heavy use of adverbs in this novel, the second most common is suddenly. Here we can see a list of all 52 sentences where he uses the word. As with the word and phrase results lists, double clicking on any one of these sentences will jump into the Word document where you can make a change. The results list usually shows a long enough context for you to decide there and then if a change is required.

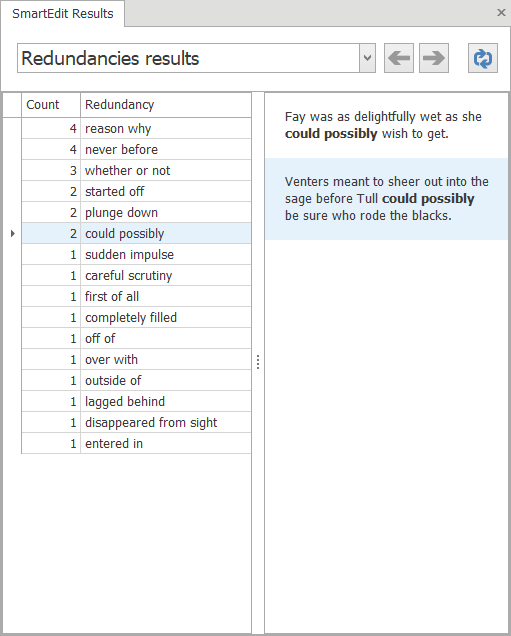

A redundancy is when you use more words than required. An example might be “fall down” or “the color red”, as opposed to “fall” and “red.” The redundancies check in SmartEdit works from a comprehensive list of redundancies and highlights each one in your document.

Unlike adverbs, the Zane Grey novel was light on redundancies. Contemporary novels that I’ve run through SmartEdit — especially unpublished novels — are far more prone to excessive redundancies.

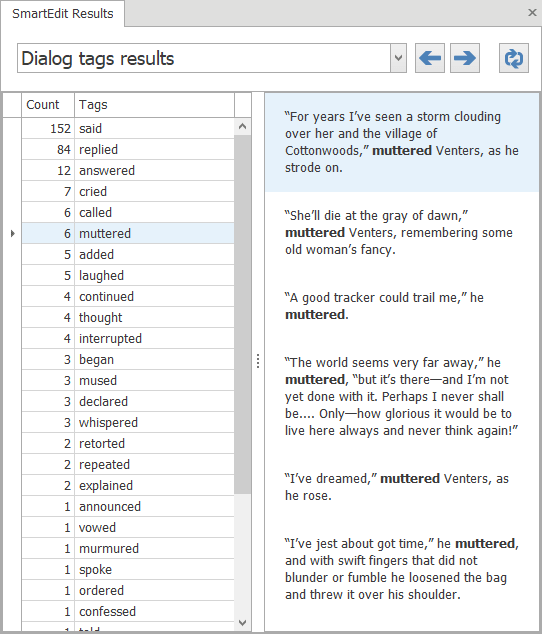

The dialogue tags checker was improved in version 6 of SmartEdit. The context sentences shown next to each result are very clear and highlight potential issues that should be obvious to any writer. The general feeling in 2018 amongst those who call themselves experts on writing is that any dialogue tag apart from said should be removed or made to explain itself.

That doesn’t appear to have been the case way back when our sample novel was published, as evidenced by all the muttering, crying and interrupting going on.

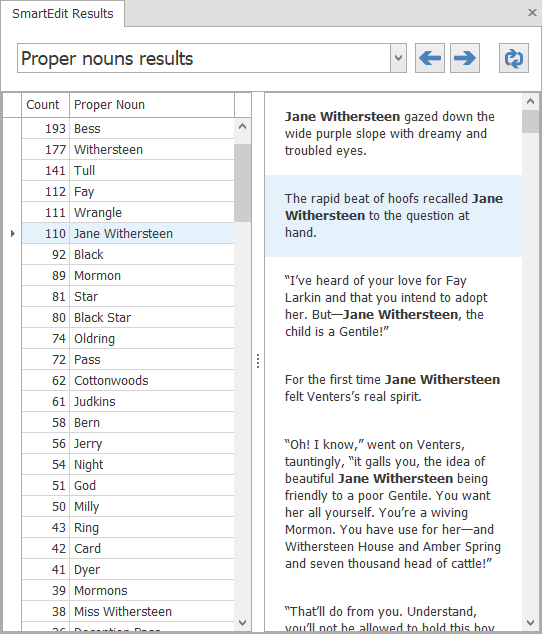

The Proper Nouns results shows a list of all proper nouns found in the document. They will often be character names, place names, company names and such. The example below shows a lot of different variations of character names, such as Withersteen, Miss Withersteen and Jane Withersteen — all the same person.

The proper nouns results list is useful for tracking down mistakes after you change a character’s name. For example: say you changed Fred Smith to John Smith and there is no other character called Fred in your novel. If the proper nouns results show an entry for Fred, you know you’ve missed at least one occurrence and need to make a change.

Extracting proper nouns is not a perfect science and occasionally one may get bypassed or a word or phrase may pop up that is not a proper noun. When this happens it often means there is some unusual or incorrect formatting in your document. For example: a missing period which makes the first word of the next sentence appear as if it were a proper noun as it is capitalized in the middle of a sentence.

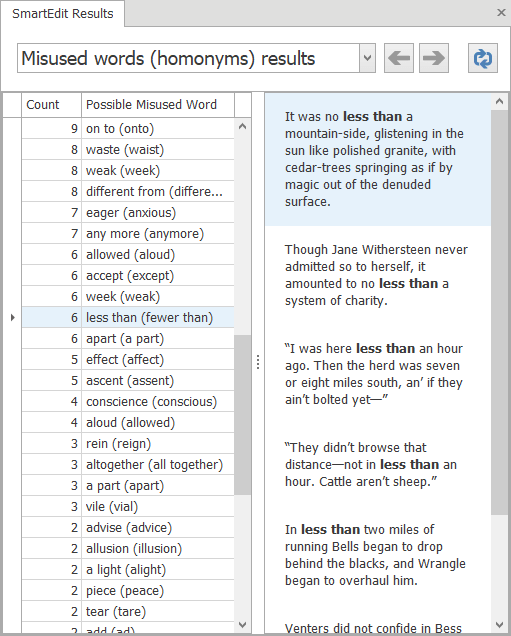

The misused words (homonyms) check is one of the more interesting checks in SmartEdit and one of the least pleasant to work through. This check looks at pairs of words that are often confused by writers, either as typos when they type the wrong word by mistake, or as errors due to misunderstanding the word or phrase itself. It’s a difficult result list to work through as it can often highlight your own imperfect understanding of the words themselves, as you scratch your head and wonder which is the correct one to use.

The screenshot above gives a good impression of the types of words that are highlighted. In most cases there will be no error, but you should go through the list regardless, focusing on words that you know you often mistype. One of my own common misspellings in this area is breathe/breath — not because I don’t know which one to use, but because I type without looking at the screen and for some reason have a habit of adding the ‘e’ when I shouldn’t.

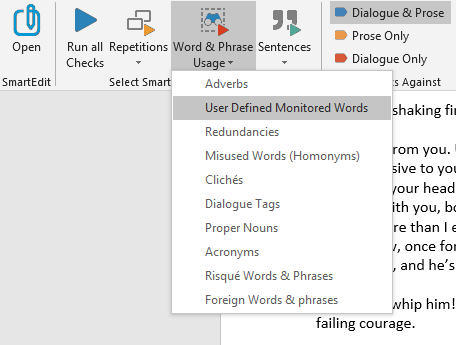

The SmartEdit survey we sent out in March told us that a few of the SmartEdit checks were rarely used and not considered that important by users. They were the Acronyms, Risqué Word & Phrases, and the Foreign Words checks.

The acronyms check is probably not that useful for the majority of fiction writers, but if you’re working on a thriller that contains a lot of acronyms — common with law enforcement and government agencies — it can be useful in identifying inconsistencies. For example: CIA, C.I.A., etc.

If you’re new to SmartEdit, I’d recommend running each of these checks individually by selecting them from the Word & Phrase Usage drop-down and working out for yourself how useful a particular check might be.